So, it’s early 2015. If you’re a freelancer like me, you may be experiencing the cold sweats of oncoming tax season. How much am I going to owe? Do I have enough stashed in my savings to cover it (LOL “savings”?!?!)? Wait… I’ve got it! During tax season, I’ll hide under some coats and hope that, somehow, everything will work out.

Okay, so maybe that’s not a bulletproof plan. I figured I should probably get this sorted out at the beginning of the year: make myself a spreadsheet with formulas that will magically tell me what I owe the government, and what I will have left over to spend on rent, groceries, bills, and piles of vintage clothing (which will come in handy in case I ever do need to hide under some coats).

As soon as I made this wonderful thing, I knew it was too useful to keep to myself, so I give you… the Freelancer Tax Calculator spreadsheet! Just click the link to download it. You can delete the first row once you’ve set everything up – it’s just to show you how it works.

(If you don’t charge HST on your invoices, download this version: Freelancer Tax Calculator – No HST. Just note that all my pics below use the other spreadsheet as a reference, and your column letters will be different.)

My spreadsheet uses my marginal tax rate to automatically calculate, for each invoice, how much I need to set aside for tax time. Find out your marginal tax rate with this tool. Just click on your province or territory, and enter the amount of income you expect to make this year (you can use last year’s total as a rough guide). Jot down the amount beside “your marginal rate is…” – that’s what you’ll be using in the spreadsheet.

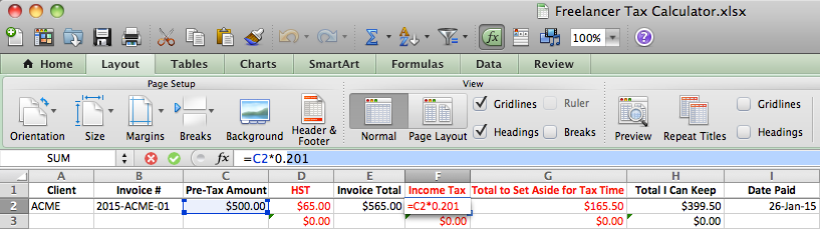

Once you know your marginal tax rate, you’ll want to adjust the formula in the spreadsheet’s red F-column, labelled “Income Tax” (the D-column if you’re using the spreadsheet for freelancers who don’t charge HST). To change the formula, click on cell F2 (D2 if you don’t charge HST) and you’ll see the formula appear in the box just above the top of the columns that has a “fx” beside it. The current formula takes the pre-tax invoice amount (in this case, $500) in box C2 and multiplies it by my marginal tax rate, 20.1%. So you can see the formula in the box says “=C2*0.201”. Highlight the “201” and replace it with whatever your marginal tax rate is (so if yours is 32.5%, put a “325” after the decimal place). Then hit enter. Boom!

Now, you’ll want to make sure that same formula applies to all the other invoices you enter in the future. To do this, click on cell F2 (D2 if you don’t charge HST) and you’ll see a little blue square appear on the bottom right corner of the cell. Click this blue square and drag it down, down, down the F (or D) column as many rows as you think you’ll need (i.e. as many paycheques as you expect you’ll get this year). This will ensure that all values in the F (or D) column will be auto-generated based on your marginal tax rate, multiplied by the invoice amount you enter into the C column in the same row.

If you charge HST but live in a province or territory that isn’t Ontario, you will want to follow these same steps to adjust the formula for HST, which currently multiples cell C2 by 0.13 (because Ontario’s HST is 13%). Once you adjust the formula to reflect your province/territory’s HST amount, make sure you click and drag the little blue square down to apply the same formula to all other cells in that column!

EDIT: Don’t forget that if you hang onto receipts, you can take advantage of tax write-offs and ITCs (write-offs of the HST you spend) for business-related things like pens & notebooks, home office expenses, and admission to exhibits/events related to your subject area! These write-offs can bring down the total amount you owe at tax time, so it might end up being less than this spreadsheet tells you. But hey, that just means you end up with a little reward in your savings account for being such a boss-ass money babe and keeping track of your shit.

And there you have it. A way to keep track of approximately what you’ll owe at next year’s tax time (disclaimer: it probably won’t be exact! but this will mean you’re not hundreds or thousands of dollars in the hole!). Every time you get paid, just plug the pre-tax invoice amount into the C column and you’re good to go. Now you can set it aside as you go and avoid the cold sweats in early 2016. Sorry I can’t help you with this year’s tax season, but let me know if you need to borrow some coats.